Age-Old Connections, Project to map 1930’s expedition reveals people, culture By Krista Allen:

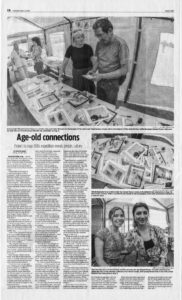

Naatsis’aan, Arizona- Seventeen-year olds Sam Hasani and Shea Hueston are telling the story of the late Max Littlesalt’s life in the form of comics, a caricature that is recognizable to readers but true to their artistic style. “What they’re doing is a graphic biography of Max Littlesalt,” said archaeologist Elizabeth Kahn, production manager and senior production editor at J. Paul Getty Trust in Los Angeles. “Shea Hueston had done these amazing watercolors and Sam Hasani is doing copy.”

Kahn is also the director of Onward Project, a nonprofit dedicated to piecing together and sharing the Rainbow Bridge-Monument Valley Expedition in the 1930’s. Kahn said the study will be published as a postcard book when completed.

Shea’s mother, Mabelle Drake Hueston, grew up in the Naatsis’aan-Rainbow City area. Mabelle’s parents are the late Harold Drake Sr. and Stella Rose Begay-Drake. Shea is Nat’oh Dine’e Bitaa’chii’nii and Toh Dine’e.

“This project is really special to me because it’s a way of celebrating my culture,” said Shea, who will be a senior this fall at St. Margaret’s Episcopal School in San Juan Capistrano, California.

“One of the Onward Project’s goals is to make Native American history accessible to the public and have stories of Natives be told,” She said. “I find a lot of value in that.

“My peoples’ stories are wroth telling, “she added. “And there’s a certain beauty to everyone– every individual story, it has a real-world relevance.”

Sam Hasani, Shea’s schoolmate, said she is interested in ways to include voices that were once marginalized and excluded in mainstream history. “And just from my perspective, coming in as a non-Native person working on Native storytelling, it’s really just been there to make sure that the Native voice is the center of the spotlight,” said Sam, who has a background in education and in oral history, “and also to make sure that exposure to Native stories be brought to the general public.”

For more than a decade, Elizabeth Kahn, Lithuania Denetso, and other has been researching the 1930 expedition, an extensive study of the Four Corners region’s natural and human history. Max Littlesalt was a Navajo-English interpreter and a guide for the scientists and students back then.

Denetso, whose family is originally from Teel Ch’inili and Tsedeeschchii, Arizona, is Littlesalt’s granddaughter. Eleven years ago, she was researching her mother, Louise Homestead, and her birth certificate in order to get a passport and online came across her grandfather who had discovered the specimen Segisaurus in Tsegi Canyon.

After that day, Denetso challenged herself to learn more about her grandfather who was born in the Arizona territory of Naatsis’aan in 1904 and died in July 1997.

Littlesalt married Gertie Austin in June 1927 after his father, the late Jim Littlesalt, visited Gertie’s father, the late John Austin, who talked about getting older and having an unmarried daughter still living in the hogan.

When Denetso started her work, she called the museums at the University of California Los Angeles where a curator connected her with Kahn. That’s when the Onward Project began.

“Since the inception of this Onward Project with Elizabeth 11 years ago, it has challenged me to reintroduce myself to extended family members, both from my grandfather’s side, Max Littlesalt and Gertie Austin,” Denetso explained.

“This project has deepened my knowledge about this particular family from (Tsegi) Canyon,” She said. “And opening up new doors and avenues and staying connected this time.”

Denetso said she’s learned a lot about Max and Gertie and their relationships and interactions with other families. “It’s been a great learning experience- it’s been good things and bad things that have happened throughout the decade,” Denetso said. “Comparing that to today with technology, 80 years ago, it wasn’t there for them,” She said. “They worked hard and got along with each other and crated friendships for a lifetime. “It’s all in good nature and we can’t change the past,” she said. “Our future is what we lead it. With this (project), hopefully, regaining decades-old friendships. And hopefully we can create that again and stay more interconnected with technology.”

Shea Hueston created with watercolors the Littlesalt family hogan and then it was printed on postcards. The old family hogan, she said, no longer stands and is just a pile of logs. “I did want to imagine the hogan for what it was and I’m sure when the Littlesalt family looks at it, they see (a restored hogan) and they don’t see the pile of (logs),” she said. “I do want to make it a touching remembrance of the past.”

Shea and Sam said the graphic biography will be about the past living in the present. “It’s basically a narrative of Max Littlesalt’s life but in a bigger picture,” Shea said. “It kind of draws into a bigger picture of Native culture, lessons that are so relevant today, kinds of interactions with the white explorers that were in the canyon.”

Sam added, “what’s really beautiful about this project is that it is telling the story of the expedition from a Native perspective of what’s commonly shown as history– anything that Ansel (Franklin) Hall said, but now you’re getting another perspective.” Ansel Hall organized and led the expedition. He was the head of education for the western region of the U.S.

“What we want to do through the book is appreciate the culture and accentuate the beauty of it, how precious and rare it is,” Shea said. “Native culture is beautiful. I really do want to focus on that book.”

Kahn and the Onward Project team were at the 54th annual Eehaniih Day Celebration where they showcased old photographs and exchanged stories with people who stopped by their booth. The team also attended last year’s celebration when they met Mabelle and her family.

In just over a year, the team has done some great things, including creating a new website (with the help of UCLA, and the Museum of Northern Arizona), which will be launched at a later date, and creating a virtual reality project.

“We’re more than ever committed to restoring history and not just having this archive of 20 to 30,000 images that only we have,” Kahn said. “We weren’t sure where the expedition men came out this way. Now we know that they were actually here a number of years… moving from place to place in the thirties,”

Kahn says she also met many people over the years who now follow the Onward Project because of it’s importance.

“We have a lot of different things going on to try to make this something that’s not just sitting around like it has been for 80 years gathering dust,” she said. “But also involving people because it’s about peoples’ stories in the end and connecting to a landscape where they are.”